2017-04-09

VoynicheseThe principal component analysis of the pages of the Voynich Manuscript suggested that the text was meaningful, and the small number of glyphs suggested that it was written in an alphabet or abjad. 15th century cryptography wasn't particularly advanced. Common tricks available to cryptographers of the period were replacement of each frequently occurring letter in the plaintext (usually vowels) with several different glyphs in the ciphertext, addition of nulls, and replacement of common morphemes with a single glyph. In addition to these, there is the question of which language the plaintext is written in. I thought it might be worth checking whether these tricks would succumb to a principal component analysis attack. As I'll show below, each language has its own signature distribution of letters/glyphs on a PCA plot, derived from vectors representing letters, each component of which is the probability of the following letter. It was thought that homophones might occur close together, though they could be chosen to avoid this by depending on the letter following, and nulls would appear at random places without upsetting the distribution of other letters on the PCA plot. To reduce clutter, I replaced endings such as |

|

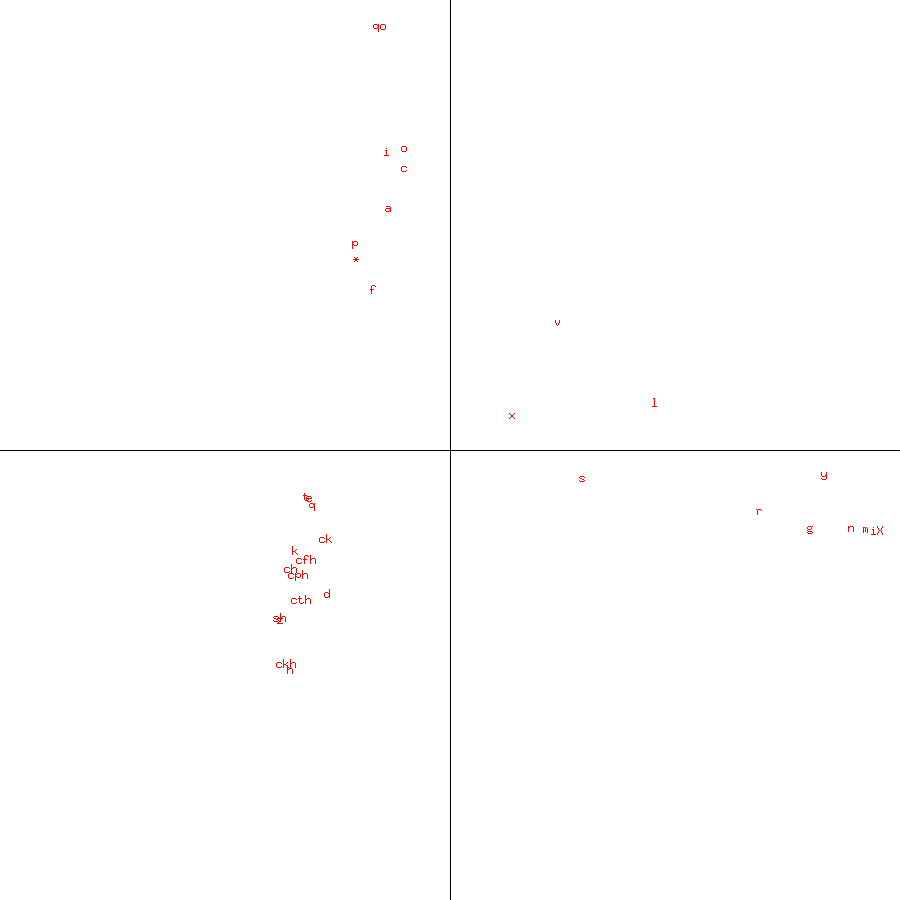

Figure 1: Plot of first two principal components for Voynich Manuscript glyphs

Table 1: Glyph frequencies in the Voynich Manuscript LatinTexts of Latin authors, Virgil, Caesar, and Pliny, were analysed. The resulting PCA plots were very similar, suggesting that they can be used to identify languages. An initial PCA showed that k and z are outliers which affect the discovered principal components. As they are rare letters in Latin, it was decided to repeat the principal component analysis without them. |

|

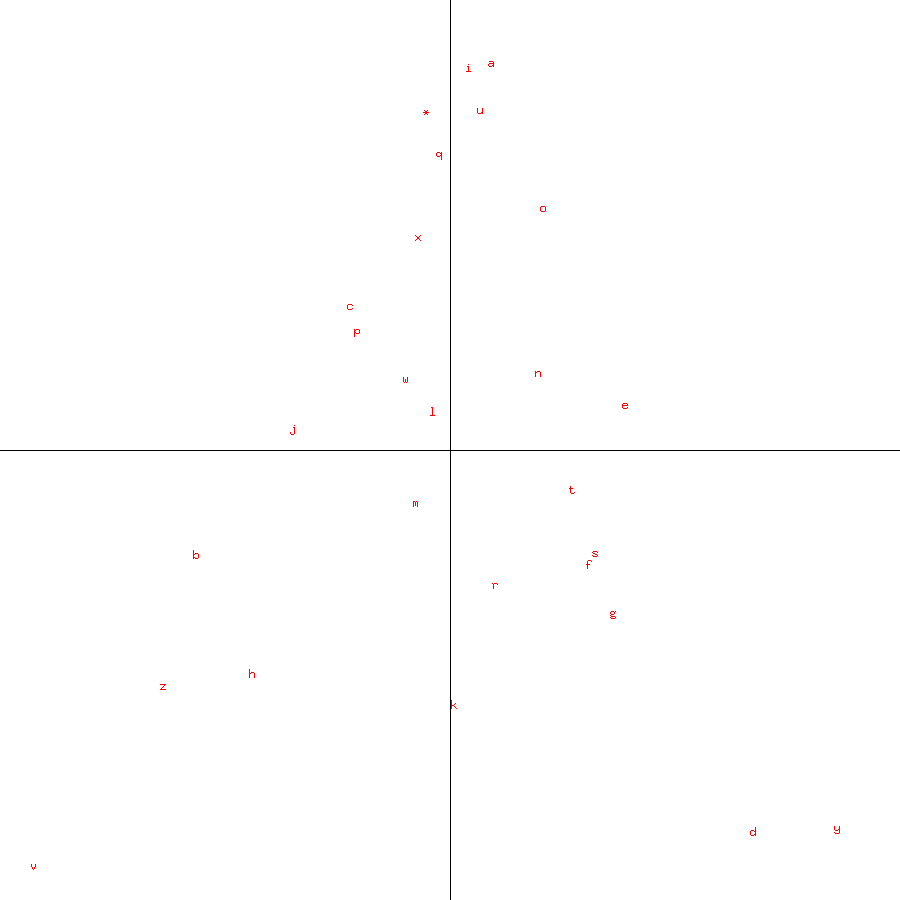

Figure 2: Plot of first two principal components for Virgil's Aeneid, without outliers k and z

Table 2: Letter Frequencies in Virgil's Aeneid |

|

Figure 3: Plot of first two principal components for Caesar's De Bello Gallico, Libri V-VIII, without outliers |

|

Figure 4: Plot of first two principal components for Pliny's Naturalis Historia, Libri II,VII,XXV-XXVII,XXXIII, without outliers After removing the outliers from the Latin texts, the plots of the first two principal components of the Roman letters are all remarkably similar. EnglishNext, texts of two authors, Charles Dickens and Jane Austen, were analysed. Again, their resulting PCA plots were very similar. |

|

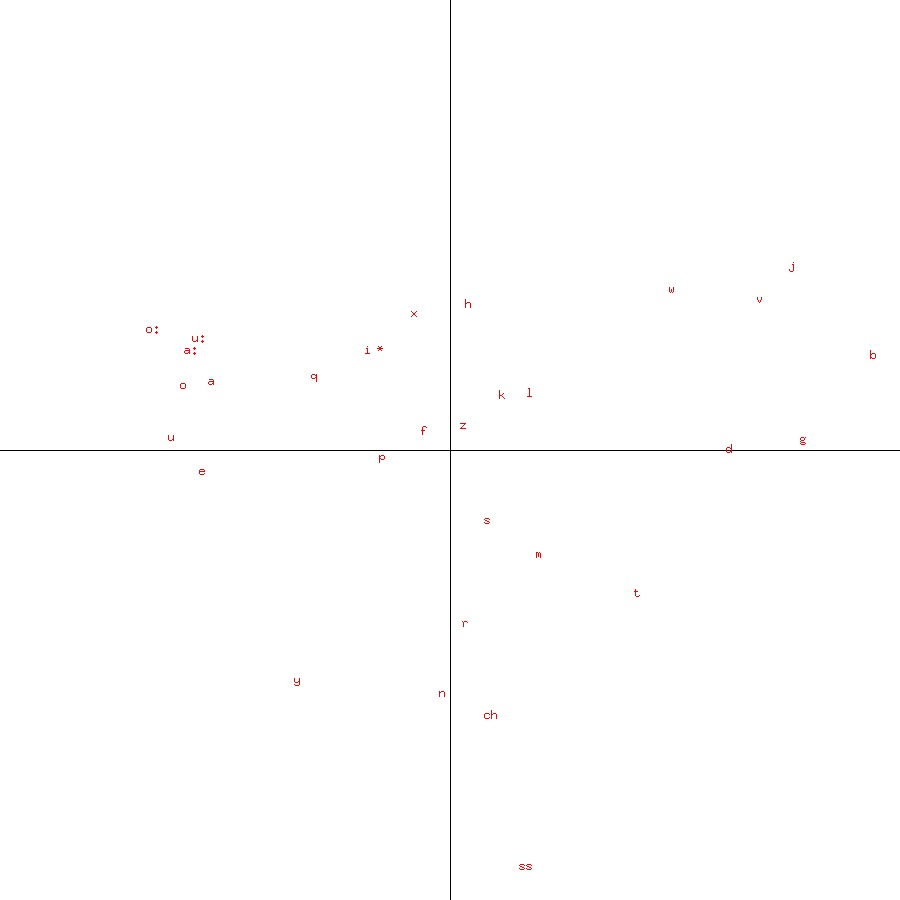

Figure 5: Plot of first two principal components for Dickens's Oliver Twist

Table 3: Letter Frequencies in Dickens's Oliver Twist |

|

Figure 6: Plot of first two principal components for Austen's Mansfield Park The plots of both modern English authors are also remarkably similar. GermanSimilar results were obtained for two German authors, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Hermann Heiberg.

|

|

Figure 7: Plot of first two principal components for Goethe's Die Wahlverwandtschaften - Kapitel 2, without outliers

Table 4: Letter Frequencies in Goethe's Die Wahlverwandtschaften - Kapitel 2 |

|

Figure 8: Plot of first two principal components for Heiberg's Charaktere und Schicksale, without outliers The plots of both modern German authors are also remarkably similar. ConclusionBecause languages can be identified by their PCA letter plots, and this is unaffected by simple substitution encipherment, both the language and substitutions can be identified by this method. However, it was not possible to identify the language of the Voynich manuscript, whose plot, with its narrow bands of glyphs, looked very different from any of the languages I examined (which, in addition to the languages shown here, also included Italian, French and Polish). |

© Copyright Donald Fisk 2017