Introduction

Handling dates isn't trivial. Here, we implement an API for the Gregorian Calendar. This isn't helpful for calculating when Chinese New Year, Passover, or Ramadan falls, but for most purposes it will suffice. The sources of complexity in the Gregorian calendar are in determining whether a given year is leap, and the different month lengths.

To simplify matters, we begin the calendar at a date

(the EPOCH) set by the user, for example Sunday, 1st January

1950. Dates before this aren't handled. The API contains three top-level

functions: indexInEpoch, which converts a given date into

the number of days from the epoch; yearMonthDay, which

converts back to a date, and dayOfWeek, which displays

the day of the week.

In the C library time.h, months start at 0 and days of the month start at 1. That is brain-damaged. Here, we will follow the ISO date convention. Months and days of the month both start at 1. Days of the week also start at 1 (Monday). Names of months and days of the week can be returned simply by array look-up.

Data Types

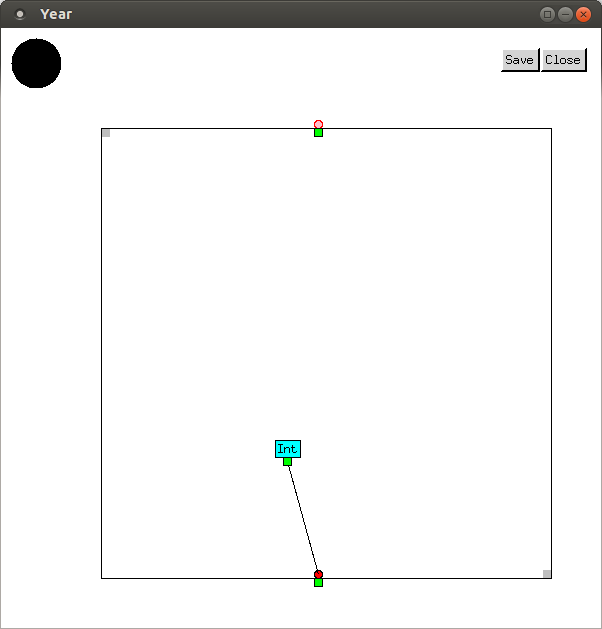

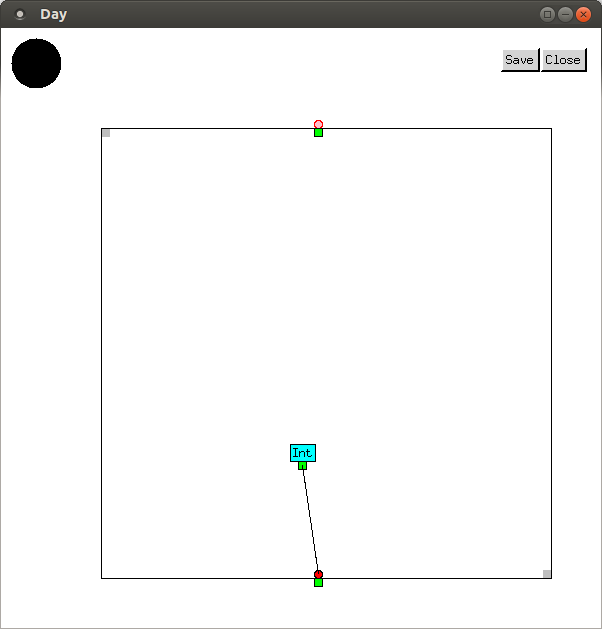

First, we define Year, Month,

and Day types. These are implemented as subtypes of

Int. This is safer than using Int, but the

extra type safety it gives us is limited. Full Metal Jacket doesn't yet

support subranges of Int, but these will be added later.

Functions

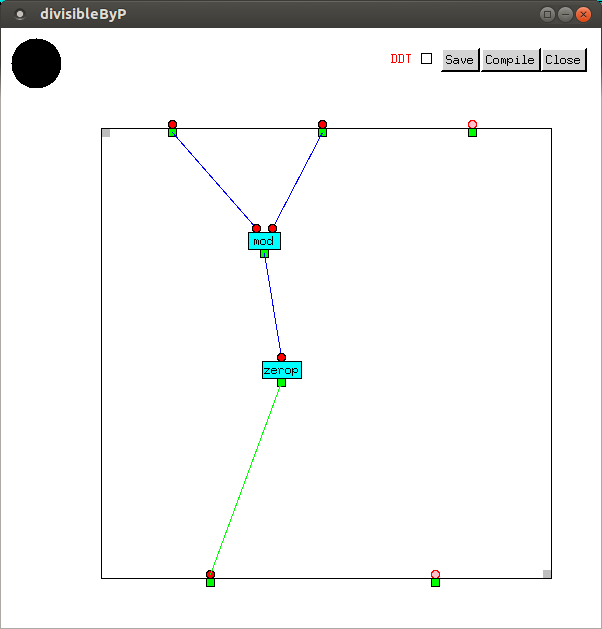

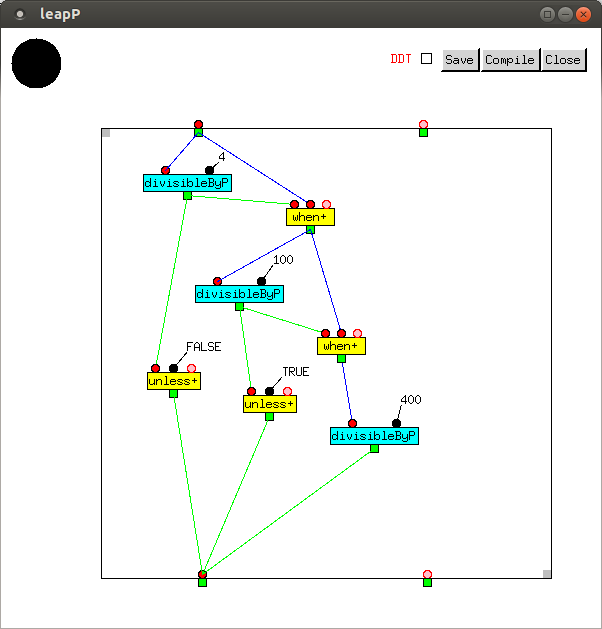

A leap year is divisible by 4, unless it's divisible

by 100 but not 400. To make the code clearer, we first define

a divisibleByP function, which outputs T if

its first input, an Int, is exactly divisible by its

second input, another Int, and otherwise outputs

NIL.

We can now define leapP, which accepts

a Year as its input, and outputs a Bool.

TRUE and FALSE are names for T

and NIL respectively, but with Boolean type.

The number of days depends on whether the year is leap.

The number of days before any month before March is the

the same in any year. From March onwards, it's one more if the year is

leap. The vector supplied to elt contains the number of days

before any month if the year isn't leap.

indexInYear returns the index of a day in a given

year, i.e. the number of days before it.

The inputs of indexInEpoch are of type

Year, Month, and Day. It outputs

the number of days from the start of the epoch.

The first value in the loop is a year, initially set to

EPOCH and incremented by one in each iteration. The second

value is the date index, initially set to 0 (its value at EPOCH),

and repeatedly incremented by the number of days in each year starting

from EPOCH. When the year which was input has been reached,

the value output by indexInYear is added to it.

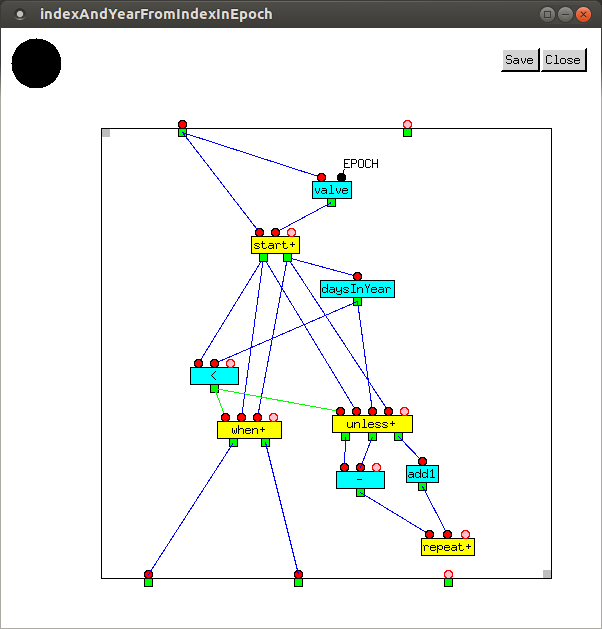

indexAndYearFromIndexInEpoch takes the number

of days since EPOCH as its input, and outputs the number

of days since new year's day, and the year.

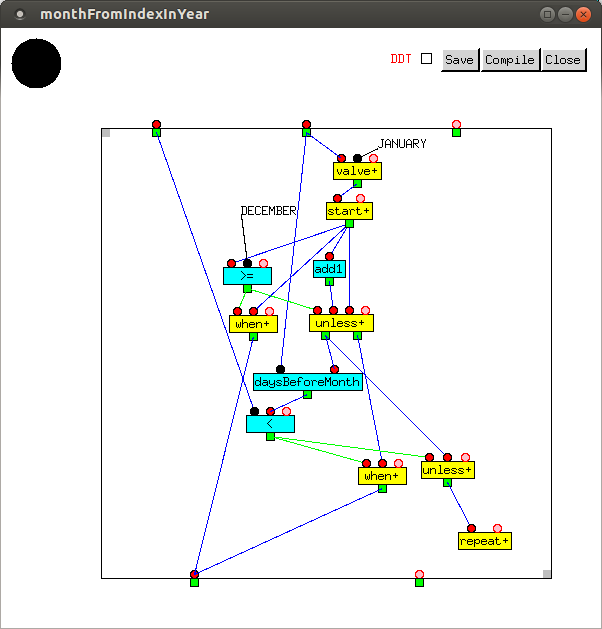

monthFromIndexInYeartakes the number of days

since new year's day and the year as its inputs, and outputs the month.

Each time around the loop, daysBeforeMonth is called, and

the value it outputs is compared against the number of days since New Year.

dayFromIndexInYear takes the number of days

since new year's day, the year, and the month, as its inputs,

and outputs the day of the month.

yearMonthDay takes number of days since

EPOCH as its input.

The day of the week is just the remainder of the number

of days since the start of EPOCH, except that it is 7 if

the remainder is zero.

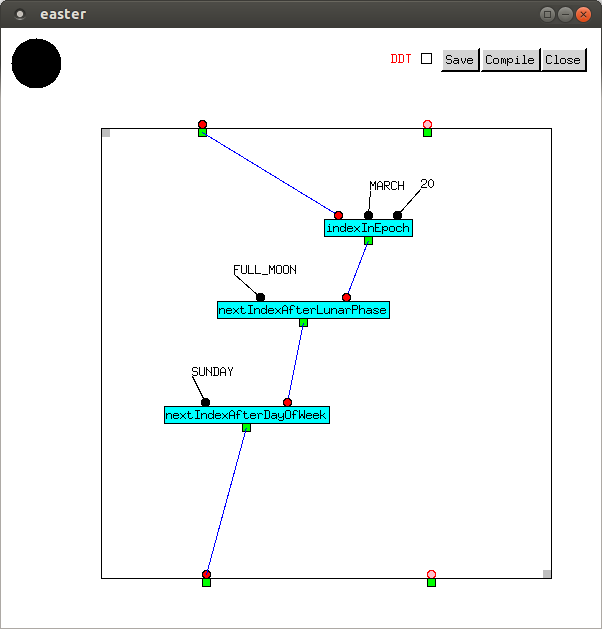

In 2016, Easter falls on March 27th. It is, of course,

a Sunday. The code in the sandbox outputs the number of days since

EPOCH, then the year, month, and day of the month, followed

by day of the week.

Bell, Book, and Candle

Determining the date on which Easter falls in a given year has always been problematic. At one point, an entire branch of the early Christian Church was threatened with excommunication over of a disagreement about how to calculate it. Computus, the algorithm currently used, is quite hairy and practically incomprehensible. Even Gauss got it wrong. There have been recent attempts to introduce a simpler mechanism.

In principle, the rule for calculating Easter

is quite simple: Easter falls on the Sunday after the full moon

after the vernal equinox, which close to EPOCH generally falls

on March 20th. At the risk of being excommunicated, I will now present

a simplified algorithm, which I have to say is wrong in 2008 and 2025.

(For this, I make no apology: if ever there was a case of

accidental

difficulty, the currently accepted algorithm for Easter is it.)

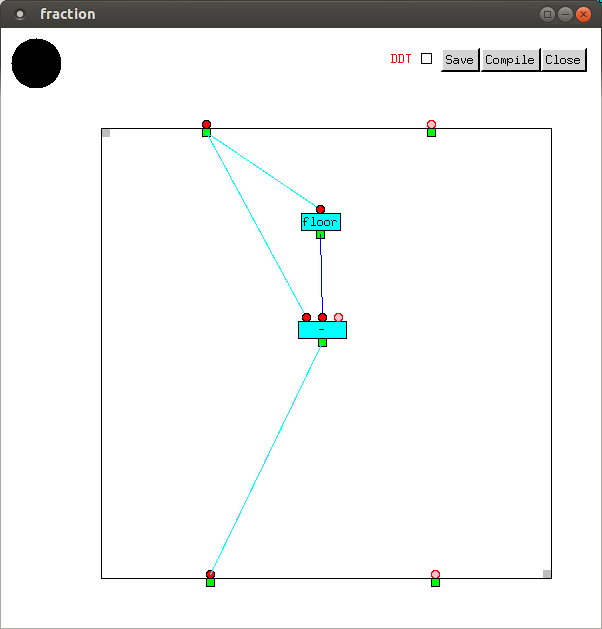

First, we write a simple helper function to calculate the difference between the value and the closest integer not higher than it.

The synodic month (i.e. the time between a given phase and

the next occurrence of it) varies only slightly, and averages

29.530588 days. So if we know the lunar phase

at the EPOCH, calculating it on any later date

is straightforward. The value returned can be any Real

between 0.0 up to but not including 1.0,

and is defined so that

| Phase | Value |

| New moon | 0.0 |

| First quarter | 0.25 |

| Full moon | 0.5 |

| Third quarter | 0.75 |

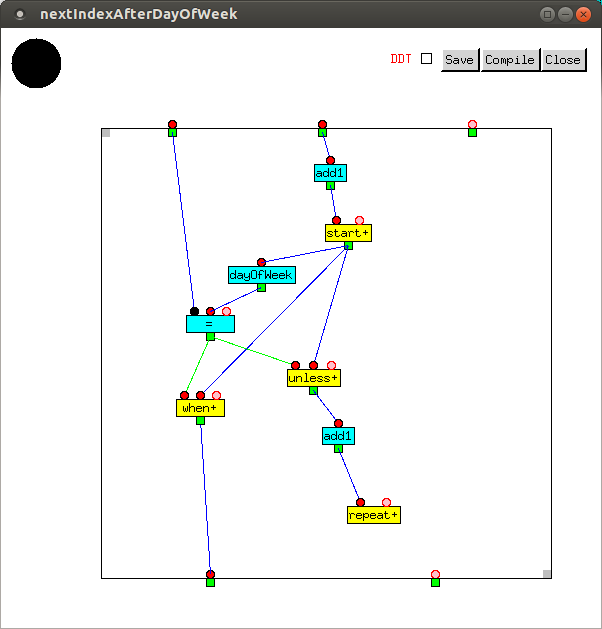

Given a day of the week (the first argument) and an index (the second argument), the next index after the day of the week is obtained by iteration, starting one day after the second argument, until the day of the week is equal to the first argument.

The day after a given lunar phase is tricky because phases

wrap around to 0.0 when a new moon is reached. This means

we should iterate starting from the difference between the lunar phase

on the day after the second argument, until 1.0 is reached

or passed, and return the index when this happens.

DAILY_LUNAR_PHASE_CHANGE is the inverse

of SYNODIC_MONTH.

easter returns the index of the Sunday after

the full moon which follows the vernal equinox, as explained above.

The constant FULL_MOON has value 0.5.

© Copyright Donald Fisk 2016